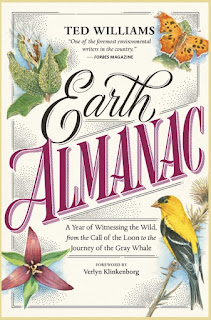

Earth Almanac by Ted Williams was due to be published on April 28, but it is now being released on September 29. I think that it is well worth the wait, but I have one solution to consider at the end of this review.

Earth Almanac is being published by a small independent press called Storey Publishing in Massachusetts. They specialize in books on nature, gardening, and how-to subjects, including an excellent line of knitting books, like One Skein Wonders. Postponing publication has been happening with many books during this pandemic, and when I reached out to this publisher about their decision, they said: they decided to delay publishing several books “because, with so many sales channels and libraries closed, they don’t want to release books into a market that limits readers’ options for accessing them.”

The book is collection of mini essays arranged around the seasons, with a longer introductory essay for each season. It’s not really a field guide, as such, but it could be used during walks to inspire you to look for the things that he so minutely observes or to make you recollect scenes from your past.

I highly recommend this book for readers of all ages for three reasons.

1. The first is that these are all very short essays, taking maybe 30 seconds to 2 minutes to read. They are completely self-contained, do not need to be read in any order, and can be picked up at any point without losing any sense of meaning. I can’t think of a better solution in this time of distraction. It was difficult to choose one essay to share, but here is this one, called “Underdogs” (page 92):

Remove the black-tailed prairie dog from its niche in our western plains and—as Americans have discovered over the past century—the whole biota collapses like the sides of stone arch. This ground squirrel, whose “dog” name derives from its bark, is called a keystone species because it provides food and/or habitat for at least 59 vertebrate species—29 birds, 21 mammals, 5 reptiles, and 4 amphibians.

The elaborate subterranean design of a prairie-dog town includes bedrooms, latrines, birthing and nursing chambers, pantries, even cemeteries. In May look for youngsters as they stumble up into the sunlight for the first time in their six-week lives. Soon they’ll be roughhousing, grooming each other, and greeting neighbors with chirps, hugs, and open-mouthed “kisses.”

Because prairie dogs eat forbs and grasses, they have been widely poisoned and shot in the mistaken belief that they compete with livestock. Studies, however, show that in aerating and turning over the soil they produce high-quality forage.

While this one focuses on the plains states, the majority deal with nature in our own Northeast region.

2. The second reason to read this is that these are exquisite little pieces that Williams writes in a fun, descriptive way that is often poetic and literary. When talking about the elusive river herring, for instance, he writes “Mostly they pass unseen, save by herons hunched over the pools like old men in ratty down jackets standing at a truckstop counter.” (page 89) He creates essay titles that reference classic poetry, “Ode to a Devil’s Urn” is one example, and he quotes from the children’s classic Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White to describe how many juvenile North American spiders disperse.

3. The third reason is that Williams writes engaging pieces that combine natural observations and scientific research that draw readers in by making them exclaim over the startling facts—did you know that chipmunks can hold up to two heaping tablespoons of corn kernels in their cheeks? He also gives how-to instructions on interacting with nature, such as finding and cooking wild leeks in the spring. And, he talks about ways to involve kids (don’t go on a nature walk, say that you’re going on an expedition) and then suggests ways to get them fully involved. Puff the Magic Fungus (page 194) is one essay that is a good example of this:

Puffballs, those fungi that appear throughout most of North America after autumn rains, on rich humus and over buried stumps, seem made for kids. The smoke that spews from the hole atop the dry, leathery husk when you tap it or step on it is spores from the already-dead fruit. So fine are these spores that they can drift to elevations of five miles and travel between continents. The giant puffball, which sometimes reaches four feet in diameter, may produce 7 trillion spores annually.These essays are magical and not to be missed. It turns out that Earth Almanac is an updated version of Williams' earlier book called Wild Moments. This is only available as an e-book and is on Hoopla, which is a library resource for ebooks, audiobooks, movies, and music.

But the magic doesn’t end there. Depending on which of the 270 species you encounter, a puffball may grow from the size of a golf ball to the size of a baseball in a single night. Moreover, the main part of the plant—the mycelium—lives underground and extends in all directions through the soil, sometimes creating a circle of puffballs above. A much older—and, some would argue, better—explanation has it that these circular growth patterns are set by the feet of dancing fairies; hence the popular name “fairy rings.” Since this theory cannot be disproved, why hasten its extinction when you are afield with young companions?

(This was used as a talk for the Richmond Memorial Library's "Lunch Time Book Chats" shared on Zoom on May 13. Thanks to the publisher and Netgalley for an advance copy.)

No comments:

Post a Comment